why we jump to the wrong conclusions (and how to avoid it)

learning to use the ladder of inference in our personal and professional lives

Have you ever been in an argument and realised later that you completely misunderstood someone else's point of view? Or have you noticed how two people can look at the same event but see completely different things? These situations happen frequently, and there's a useful explanation for that: the ladder of inference.

The Ladder of Inference was introduced by Chris Argyris and Donald Schön in the 1970s and popularised by Peter Senge in the 1990s. Originally developed in organisational research, this framework helps us understand how we move from observing facts to reaching conclusions and ultimately acting - often unconsciously influenced by bias, experience, and beliefs. Today, I will just give a quick introduction to the subject. Then, in the following posts, I will slowly start using this model in other tools that help us be better leaders, communicators, and decision-makers.

Before we jump into it, let's spend a few words on what it is and why we should be interested in it.

What is the Ladder of Inference?

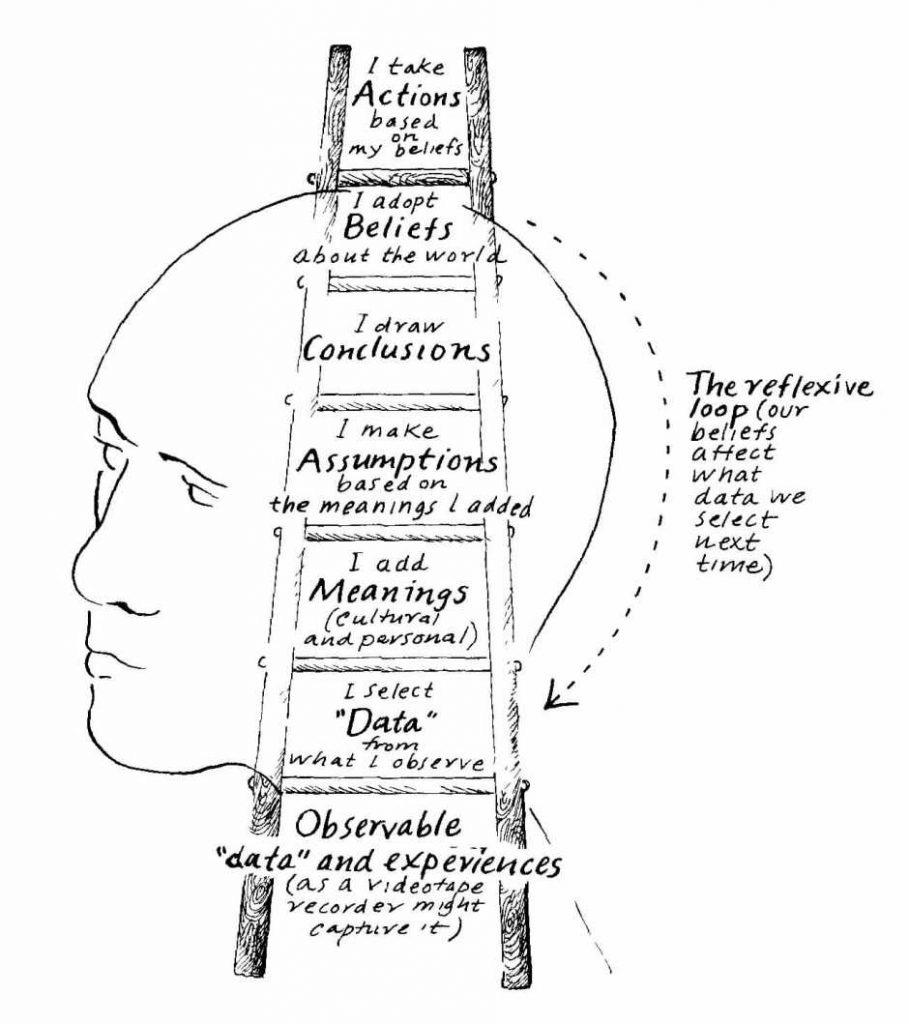

We can call it a model or framework of how humans process information from observation to conclusions and actions. It explains how our actions/decisions are not based on objective reality but are influenced by our past experience, mental models, environment, and cognitive biases. This is visualised through the rungs of the ladder.

The rungs in the "ladder" represent how we process information step-by-step; we start from the bottom and move higher by going up rung after rung:

Observable Data – What actually happens

Select Data – What we specifically notice

Interpret Meaning – How we add context

Make Assumptions – How we explain events without evidence

Draw Conclusions – How we form our personal narratives

Adopt Beliefs – How repeated conclusions turn into beliefs

Take Action – How those beliefs influence behaviours

This model is popular because of the visual representations that go through our thinking process. If we can visualise how we move from observation to action, we can examine our reasoning and challenge our assumptions to make, in the end, a better decision.

Before jumping into the rungs of the Ladder of Inference, Let's unpack a few things mentioned above, as this will come in handy when we are working with rungs.

What is a mental model?

A mental model is basically an internal picture or understanding we have in our mind about how something works. It's our personal representation or explanation of a process, concept, or how the world operates. We constantly use mental models to simplify complexity, make decisions, predict outcomes, and take actions. Essentially, they're like mental shortcuts or maps that help us navigate everyday life.

What is cognitive bias?

Cognitive bias is basically when our brains take shortcuts or make assumptions, causing us to misunderstand situations or make irrational decisions without even realising it. It's kind of like our brain playing tricks on us.

For example, imagine you read online that coffee has health benefits. If you love coffee, you'll probably trust and remember this information. But if you later come across an article saying coffee can have negative effects, you might dismiss or ignore it because it contradicts what you prefer to believe. This is called confirmation bias—we tend to accept information that supports our existing beliefs and reject information that doesn't fit them.

Ladder of Inference

The only steps visible to others are observable data and actions, everything else, sits in our head and is not visible or communicated to anyone else if we will not make it explicit. Lets dive in into rungs and a thing called The Reflexive Loop.

1. Observer Data: "What's Happening Around Me?"

At the very bottom of this ladder is reality itself—just facts, details, things we can actually see, hear, or record. These are events precisely as they happen, without any spin or interpretation yet. Think of this as raw footage straight from a camera, with nothing edited out (so not something on Instagram), a list of numbers, etc.

Example:

You're in a meeting, and your colleague Tom looks repeatedly at his phone while you're presenting your new idea.

2. Select Data: "What Am I Noticing?"

Because we're human, we naturally focus on specific details and miss others. We can't see, hear, or pay attention to everything at once. So, we subconsciously filter out data based on what's relevant or important to us right now, influenced by our past experiences, biases, beliefs, and current priorities. Two people watching the exact same event might notice completely different things.

Example:

You specifically notice the moments Tom looks away at his phone, ignoring times when he nods or makes eye contact - focusing clearly on his distracted behaviour.

3. Interpreting Meaning/Add context to data: "What Does This Mean to Me?"

At this step, we interpret or give meaning to what we've observed. We start telling ourselves a story based on our background, culture, experiences, and perspective. It's as if we're translating facts into our own language (trying to put what we observed and selected into our own words), making sense of it through our individual lens.

Example:

You interpret Tom's glance at his phone as boredom or disinterest. You tell yourself, "He's obviously uninterested in my presentation. Maybe my ideas aren't very good."

4. Make Assumptions: "Why Did That Happen?"

Now, we start guessing and filling in any missing pieces. If we don't have all the information (which we rarely do!), we naturally create assumptions — often automatically — to explain why things happened the way they did. This is where we guess about other people's intentions, feelings, or motivations — even without confirming our guesses.

Example:

You assume Tom doesn't value your input or is intentionally disrespectful. You start to think he's not taking you seriously.

5. Draw Conclusions: "What's My Explanation?"

Here we put all our interpretations and assumptions together to form a clear conclusion or explanation about what's happening. Essentially, this step creates a neat story in our minds, helping us feel we fully understand the situation - though, honestly, we often have less information than we think.

Example:

Based on your assumptions, you conclude Tom is unsupportive or not a team player - someone who doesn't appreciate collaborative efforts.

6. Adopt Beliefs: "What Does This Say About the World?"

The more often we come to similar conclusions, the stronger these become as beliefs. These beliefs shape our perspective and worldview and begin to feel like facts. Over time, they strongly influence how we view new situations, making it easy to get locked into our particular way of seeing the world.

Example:

You gradually form a belief that Tom is generally not collaborative or trustworthy in professional settings. As this belief grows, you begin expecting similar behaviour from Tom in future meetings.

7. Take Action: "What am I Going to Do?"

Finally, based on our beliefs and conclusions, we act. These actions reflect our interpretation of reality rather than reality itself and can have real consequences and create new situations that others (and us) observe and interpret — and the whole cycle begins again, shaping not only our experience but the reality experienced by others.

Example:

Based on your belief, you might avoid inviting Tom to critical discussions or become cautious about sharing further ideas with him - impacting how you engage and communicate with him in future interactions.

The Reflexive Loop: "Why We Keep Seeing What We Expect"

Reflexive Loop simply means our beliefs guide what we pay attention to, and what we pay attention to reinforces our existing beliefs.

Here's how the cycle works in everyday terms:

Beliefs shape what we notice: Our current beliefs affect what stands out. We tend to notice things that confirm our existing views and often overlook information that challenges them.

We interpret information based on what we already think: When we notice data fitting our beliefs, we interpret it in a way that supports those beliefs. It's as if our mind highlights the "proof" we already expected.

Our beliefs get stronger: Because we're constantly interpreting situations in line with our existing views, our beliefs strengthen over time - after all, we're seeing "evidence" everywhere!

We repeat the cycle: Stronger beliefs mean an even narrower focus on data that matches our worldview, further limiting our perspective.

If we aren't aware of this loop, it's incredibly easy to become locked into rigid viewpoints. We might unknowingly block out evidence that challenges our thinking, making it harder to learn, grow, and understand different points of view. The good news? Just being aware of this cycle helps us step off the loop and see things more clearly.

Example:

Because you've formed a belief that Tom is unsupportive, you'll naturally pay extra attention whenever he does anything that confirms this belief (not returning emails quickly, disagreeing in meetings). You'll interpret new actions according to this belief, reinforcing your perspective and further deepening your conviction, thus creating a self-sustaining cycle.

How can we use the Ladder of Inference?

When making decisions or forming judgments, we can try to identify which rung of the ladder we're currently on. Are we working with observed data, or have already moved up to assumptions or conclusions? Being aware of where we are in the process helps you evaluate whether we've skipped important steps or made assumptions in our reasoning.

Suppose we find ourselves at the top of the ladder, making decisions based on beliefs. In that case, it can be valuable to deliberately work our way back down to examine the data we have selected, how we interpret it, and what assumptions we made along the way. This process of descending the ladder allows us to rebuild our reasoning on a more solid foundation.

When communicating with others, especially in situations where differences of opinion exist, explicitly share thought processes. Explain what data we're basing our conclusions on, how we're interpreting that data, and what assumptions we're making. This transparency helps others to understand how we come to a specific decision. Also, it helps to align if we have differences in conclusions or even selected data. In the next post, I will show how we can use it with other tools and practice this on paper before testing it against humans.

Summary

The ladder of inference provides a powerful model for understanding how we process information and make decisions. By visualising our thinking as a climb up a ladder—from observable data through selection, interpretation, assumption, conclusion, and belief to action—we gain insight into how easily we can drift from factual reality to subjective judgment.

In today's complex and fast-paced world, where decisions often need to be made quickly with limited information, the ladder of inference is a valuable tool for improving our thinking process. By becoming aware of how we move through rungs, we can make more deliberate choices, challenge our assumptions, and communicate more effectively with others. This awareness doesn't guarantee perfect decisions, but it does help us avoid many of the pitfalls that lead to poor judgment and unnecessary conflict.

Understanding and applying the ladder of inference is not just a professional exercise but a practical skill that can enhance every aspect of our personal, leading to better decisions, stronger relationships, and more effective problem-solving.

I'd like to challenge you - next time you catch yourself forming a quick judgement, try pausing and reflecting—at which rung did you hop onto the ladder? Share your insights or experiences in the comments below. I'd love to hear them!